Slow is the new fast in business of innovation commercialization: SFU Beedie study

May 01, 2018

SFU Beedie research examines the role of licensing speed in the success of technology commercialization

The pace of innovation remains a critical topic for business leaders. Historically, the symbolic role of speed in technological advancement and business innovation has been highlighted by book titles such as “Fast Innovation” and “Fast Second”, and even popular magazines like “Fast Company.”

Yet a newly-published study from Simon Fraser University’s Beedie School of Business and published in the Journal of Engineering and Technology Management makes the case for a slower pace in certain situations. Entitled “Licensing speed: Its determinants and payoffs,” the article was authored by Ian McCarthy, Professor in Technology and Operations Management/Strategy, and Karen Ruckman, Associate Professor in Strategy.

Counter to arguments for a universally fast-paced innovation strategy, findings from the SFU Beedie study suggest that for the commercialization stage of the innovation process, particularly in biotechnology, it is beneficial for certain licensors to slowly and carefully license-out patented technologies.

The authors looked at licensing data from the biopharmaceutical industry over a 15-year period—examining both licensing speed and the payoff from the licensing agreements.

Commercialization, and licensing in particular, is a significant stage of the innovation process, as it captures financial value from innovation activities. Within the United States alone, the annual value of licensed technologies increased from $50 billion in 1997 to $138 billion in 2014.

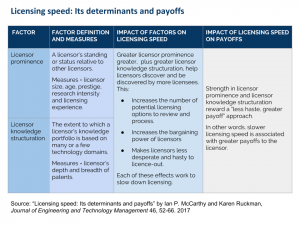

It turns out that more prominent (i.e., large, prestigious and experienced) companies tend to be slower at licensing. According to McCarthy and Ruckman’s research, a company’s “halo effect”—created through these variables as well as the depth and breadth of the company’s technological expertise—plays a key role in the pace of the licensing process. A licence holder takes longer to license-out in at least three ways.

Firstly, they attract a greater number of potential licensees. It takes more time to review and shortlist these, and subsequently to negotiate and make a deal. Secondly, due to their prestige and size, they are not desperate to rush into a licensing agreement. Third, they are in a position of power to carefully and methodically choose partners to work with and maximize their opportunity. And, it turns out, they get better royalty rates and economic returns by being slow at licensing.

“With licensing, you do care who owns and exploits your technology,” said McCarthy. “You want a licensee who is going to commercialize it in a way that maximizes value. That means you may take time to be fussy, and screen and evaluate buyers so that you can maximize the returns you get.”

McCarthy admits this might go against some preconceived notions about the importance of fast innovation and the commercialization of patents. Because patents are time-protected, one might assume that they should be dealt with quickly. However, the most prominent licensors don’t see it this way. “We predict and find that strength in licensor prominence and licensor knowledge structuration rewards a ‘less haste, greater payoff,’” he said.

“These factors help licensors to discover and be discovered by licensees, resulting in an abundance of licensing opportunities that not only increases the size, complexity and duration of the licensing out-task, but allows licensors to take their time to review, negotiate and select the most attractive offer,” he said. “That’s why the process is slower, and why slower is better.”