CPA Innovation Centre: How technology affects mindfulness

Apr 22, 2016

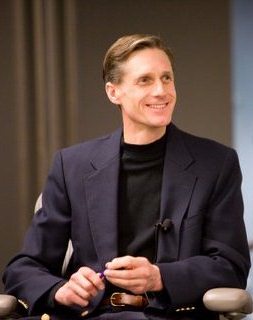

Pierre Berthon, McCallum Graduate School of Business, Bentley College, MA, delivered a special presentation at the Segal Graduate School on technology’s effect on mindfulness.

Technology is increasingly embedded in our everyday lives, yet in addition to the positive effects that it is intended to have it can also have negative side effects – one of which is a significant detrimental impact on our attention spans.

This was one of several fascinating insights presented by Pierre Berthon, McCallum Graduate School of Business, Bentley College, MA, at a special CPA Innovation Centre research presentation at the Segal Graduate School on April 21.

Berthon delivered an engaging presentation on technological mindfulness based on research he had conducted in collaboration with Beedie School of Business faculty Ian McCarthy, Jan Kietzman and Leyland Pitt, along with Tamara Rabinovich, of Bentley University.

Technology has changed the way people live, but there is a danger that it now has too much influence on our everyday lives. Berthon himself gave up wearing a watch at a young age due to the tendency for the watch to control him.

“Our relationship with technology is tricky,” he said. “It is ambivalent – we absolutely love it – and yet it controls us, guides our life, and interferes with our life.”

Berthon cited several examples indicating that technology is having profound negative side effects on society: since 2000, the placebo effect has dramatically increased in the US as a result of the prevalence of pharmaceutical advertising on television; studies on schoolchildren have demonstrated a huge increase in narcissism since the year 2000; and IQs have also dropped since the year 2000 – albeit only in the reasoning component of the test.

Indeed, prior to the year 2000, the average attention span in humans was measured at 15 seconds. Since then, however, it has dropped by more than half to seven seconds.

Many people rely on their GPS systems to the point where it overrides our own sense of safety. Studies have indicated that people who rely heavily on their GPS systems have shown significant shrinkage in their hippocampus – an area of the brain that controls spatial awareness but that must be used frequently to maintain its health.

Discussing a framework that deals with the types of reality society has at its disposal, Berthon noted that the further away you get from embodied reality to virtual reality, the more freedom you have to create your own degree of freedom.

Few people post unflattering pictures of themselves on Facebook, for example, but instead edit them to make them look good. Studies have indicated that people who spend a lot of time on Facebook become depressed, with a hypothesis suggesting that this is due to the edited highlights they see of other users’ lives making them feel inadequate and jealous.

“But herein lies the sting,” he said. “The more disembodied we become, the less we have to face the reality we are faced with. The more there is this disjunction, the more there are issues.”

Three examples of this technological paradigm demonstrate what technology is doing to us. The demise of vinyl records in the face of MP3 music files has caused a change in music itself. Now songs need to hook listeners immediately or they will stop listening. Text on the internet also differs to that in a book. Hypertext always has readers searching for more. While text in a book could be compared to a room, hypertext is like a door – it brings you to somewhere else.

The advent of electric power steering as opposed to hydraulic power steering also represents a fundamental change. While hydraulic steering required human input, electric steering does not even require a driver – it has the capacity to drive the car itself.

Berthon expressed his interest in studying Creative Communities (CCs), groups of people who actively manage their technologies in new ways. The Amish, for example, do not shun all technology, but are instead extremely selective in their use of it. They select their technology based on two goals: keeping the community together, and what type of person you become by using a piece of technology.

The increasing influence of technology has impacted on our attention spans. There are two types of attention: endogenous, where the person chooses what to focus on; and exogenous – or hijacked – where a stimulant takes your attention away from the task you were focusing on. Social media relies on hijacked attention.

“These platforms are primarily advertising platforms, designed to get as many views as many times a day as possible,” he said. “They have the best minds in the world working on hooking you in. There is also social pressure – a fear of missing out. And biology plays a part. When we are interrupted y something that grabs our attention we get a big release of dopamine. It’s the anticipation hormone. We become addicted to it.”

For more information on the CPA Innovation Centre visit beedie.sfu.ca/cpa-centre

About Ross MacDonald-Allan

Twitter •